4th Annual Single Wing Conclave

January 31st, 2005

Friday, March 11th & Saturday, March 12th, 2005

Burke Auditorium

King’s College

133 North River Street

Wilkes-Barre, PA

4th Annual Mixer

Thursday, March 10th, 8PMish - ???

TGI Friday’s

Adjacent to the Holiday Inn-Wilkes Barre

Registration:

Individual - $25 in advance, $35 after Monday, March 7th

Staff - $15 each (staff of 3 or more), $25 each after Monday, March 7th

PLEASE EMAIL ME AT [email protected] WITH NAME(S) AND HOW MANY IF YOU ARE PLANNING TO ATTEND!!!

Registration includes room usage fee and continental breakfast each morning. These fees are NOT negotiable. Even if you don’t eat at Burke, you will pay for breakfast.

Please mail check or money order w/ names(s) attending to:

Todd Bross

418 Cedar Avenue

Sharon, PA 16146

Questions - email me at [email protected]

Lodging: Feel free to make your reservations anywhere, but we have made the Holiday Inn on Kidder our unofficial base camp. Its a great opportunity for after hours skull & BS sessions with many coaches, video swapping, plus just having fun! (ask last year’s “survivors”)

Holiday Inn (Arena)

880 Kidder Street

Wilkes-Barre, PA 18702

1-570-824-8901

Fax: 1-570-8249310

Email: [email protected]

Check-In Time: 3:00 PM

Check-Out Time: 11:00 AM

NOTE: There are no group rates. Mention you are attending a conference at King’s College and you should get a $60ish/nite rate.

PRESENTATIONS: We will aim for 4-5 presentations each day. I am now seeking volunteers willing to put together an approximate 90 minute presentation (including video & Q&A). I will be cold calling a few of you specifically.

Criteria: The main focus of the Conclave is 2 fold. 1st & foremost, the focus has and will be on “How To” do various aspects of single wing/direct snap offenses (Sorry - QB’s need not apply). Presentations should dwell heavily on actual demonstrations, and not rely on X’s & O’s. This is a must. 2nd, youth coaches get equal opps & props with their high school counterparts.

FRIDAY, MARCH 11th:

Continental Breakfast: 7:30 AM

Presentations: 8:00 AM - 5ish

AM:

“Installing Cross Training for Your Backs in the Spin Series”

Sean Orr

Head Coach, Williamson Trade School

Media, PA

PM:

“The Buck Lateral Off the Power Series”

Tom Lewis

Head Coach, Plymouth High School

Plymouth, Ohio

“Installing the Single Wing for 1st Time Youth Coaches”

Richard “Air” Flores & staff

Head Coach, Santa Ana Redskins

Santa Ana, California

SATURDAY, March 12th:

Continental Breakfast: 7:30 AM

Presentations: 8:00 AM - 5ish

AM:

“The 1/2 Spin - Counter Series”

Dr. John Ward

Head Coach, Union High School

Union, North Carolina

PM:

“Option from a Direct Snap”

Deron Bayer

Assistant Coach, Housatonic High School

Housatonic, Connecticut

“Free Forum”

- Last presentation of the Conclave. All are welcome to present/discuss/ask small topics. Very popular last year.

Attendees (as of 2/23): Frank Amato, Brandon Baker, James Barg, Deron Bayer, Jeff Bayerl, Chris Beil, Jim Bremer, Tremayne Brooker, Todd Bross, Mark Cohen, Denis Cronin & staff, Tom Culliton, Tom Davis, Nick DeStefano, James Flores, Joshua Flores, Richard Flores, Mike Garcia, Dan Gobbie, Ryan Good, Mark Gouveia, Tom Gumper, Todd Hagemeier, Scott Harbison, Dave Harms, Steve Havens & staff, Tom Hill, Chad Hollwedel, Don Isabelle, Fritz Jaquey, Pete Kopecky & assistant, Greg Kuhn, Brett LeGault, Dan Lerum, Tom Lewis, Mario Meissner & a friend, (from GERMANY!), John Minteer, Maurice Moody & staff, Mark Moran, Sean Orr, Vin Pettis, John B. Reed, Anthony Rempel, Justin Sayko, Rob Schiller, Darin Scriber, Ken Senisi, Paul Shanklin, Doug Shiner, Jeff Slatcoff & staff, Dave Upshue, Clyde VanEpps, Jamie Wagner, Dr. John Ward, Keith Weaver, Kyle Wieland

PLEASE check this thread for updates!

See ya at TGI Friday’s on the 10th!

Direct Snap Football and Me

January 27th, 2005

I got my start in coaching in 1974 at the age of 16, preparing for the “powder puff” football game scheduled for November between the junior and senior class girls. Right before the end of my sophomore year in June, I made a trip down to the San Francisco main public library to see if I could find an offense that was simple and effective for people who had never played organized football before. I came away with two gems: Dr. Kenneth Keuffel’s Simplified Single Wing Football, and Dutch Meyer’s Spread Formation Football. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the two offenses would complement each other, while not demanding too much additional learning for any of the players.

That summer, I also got an offer to assist with the coaching of a Police Athletic League club, the Seahawks. Since they practiced fairly close to my high school, I figured I could give them a hand even while I was coaching the girls and trying out for varsity football for the first time (up until the early 1970’s, San Francisco’s public high schools were three-year programs, and I spent the fall of my sophomore year playing my first organized football on the sophomore team, which competed against frosh/soph teams from around the Bay Area). Of course, I had NO IDEA what I was getting myself into…

August rolled around and the head coach of the Seahawks got reassigned out of San Francisco by his employers. The assistant was promoted to HC, but since he only ever handled the defense, he asked me if I could help with the offense. With Dr. K and Dutch in hand, I confidently replied that I could get a core unbalanced single wing offense installed in two weeks. The crazy thing was, I did. On both teams.

With the PAL club, the focus was on the power off-tackle play, and how to block the most common youth defenses of the day — the 6-2 and 7-1 (7-Diamond). That took an afternoon, after which we worked on a fullback wedge, the optional running pass (in lieu of a sweep), a wingback reverse inside tackle, and one dropback pass (Dr. K’s deep wingback cross play). Within six days we had the offense installed, and fortunately the head coach knew enough to rep the heck out of all five plays for the two weeks that remained before our first game.

Meanwhile, the girls team presented different challenges. The basics needed even more time than they did with the 10-11 year old PAL team, obviously, and then there was the flag question. Could we run single wing football in the flag context? As it turns out, yes. The optional running pass was an awesome play from the start, with edge defenders finding themselves in an impossible bind the very first time we ran it. It put the ball in the hands of our best athlete, our tailback, and broke her outside of containment with the ball and receivers in front of her — on a monotonously regular basis. Beyond that, we put in a wide wingback reverse with sweep blocking and a fullback seam buck. That was it. I started to install the same dropback game that I did for the PAL club, then suddenly slapped my forehead and remembered the TCU Spread. Why not give the defense a very different look and set of problems with little additional coaching for the girls? (Always an important consideration, given that we had an hour a week to practice if we were lucky).

So in went the Dutch Meyer offense, and suddenly we were throwing dropback passes with receivers all over the field. We quickly adapted the fullback seam buck, reasoning (correctly) that it would have a much better chance of succeeding from Coach Meyers’ Normal formation than it would from the single wing. Then I had the bright idea to add the optional running pass and a fake reverse optional running pass to the TCU Spread, and there we had our offense — two formations and seven plays. There was enough commonality in the two arsenals that players basically only had to remember where to line up in which formation. That took three weeks, mind you, but we got it done.

Just to prove that auto-plagiarism is the finest kind, I introduced the TCU Spread and its deep passing game to the PAL club. We quickly got the team lined up and running two dropback passes, and suddenly the offense seemed to gel. Our kids knew we were doing some pretty radically strange stuff, and they really enjoyed it. “Seahawk Ball” stood for something different and exciting, and we had a really good vibe going into our first game.

And then there was the varsity football team. I got my butt kicked in double-sessions as I rarely had before in life, and between the start of school and the physical drain of football, I was suddenly up to my ears with football teams to coach. I explained to the head coach that my commitment to the Seahawks would be reduced in terms of attending practice during the week, but that I would be there for every Saturday afternoon game (Lowell’s varsity played Friday afternoons). He said he understood perfectly (and I think he knew I was biting off more than I could chew). We had the offense up and running, and he was confident he could rep it and fine-tune it during the week. As it turned out, he was right. The Seahawks had the best season in their brief history, going 6-1 after having finished 1-6 the year before with substantially the same talent. The single wing ground game and the TCU aerial threat combined to confuse defenses, and ended up averaging five touchdowns a game.

Back to the girls — they got the plays down very quickly, and our tailback discovered she enjoyed the feeling of sitting back in a “shotgun” offense and finding open receivers. The Dallas Cowboys were just bringing their shotgun offense into prominence, and as a result we nicknamed her “Staubach”. The one game we actually played was an anti-climax, since it was rigged every year by the referees (two borderline alcoholic math teachers) so that the seniors won, but we made them sweat. After the third long touchdown was called back for phantom clips, I huddled the girls on the sideline and explained that there was no way they were going to let us win, but that we were going to lose in style. The result was two more “clips” on sure touchdowns, and a huge moral victory for the Class of ‘76. (The next year we won 52-0 with no help from the referees.)

My first year in varsity football was also a success, reaching the semi-finals in Kezar Stadium only to lose to the eventual champs, O.J. Simpson’s old high school. I gained a great deal of knowledge about the game, and started my acquaintance with the Wing-T that continues to this day. Most of all, however, I felt the first stirrings of a love for coaching that I have never left behind, and as a result I will always have a warm place in my heart for direct snap football.

If I had to do it over again, mind you, I would install the half-spin series from Steve Owen’s A formation…

It’s the Spin That Wins!

Ted Seay

seayee at hotmail dot com

North Carolina High School Football Nostalgia

January 24th, 2005

Submitted by Keith Neal

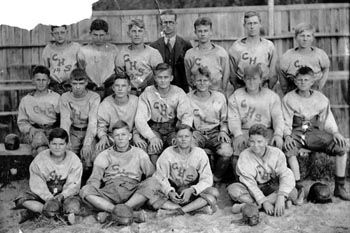

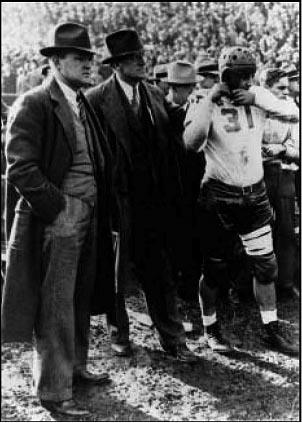

1926 was the first year that Cherryville High School, NC was recorded as playing football. This was a glass negative photo of that team. They are recorded as winning the first game they played and probably the first game that most of the team members had ever seen.

This photograph is not labeled but given that the players look the same and the uniforms are the same I assumed this was the 26 team in an action photo.

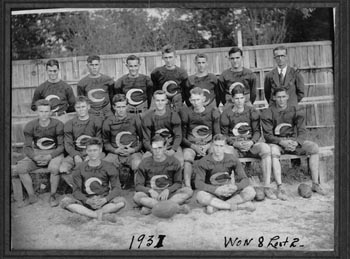

The 1927 team had new jerseys. This may seem a small matter but it is an indication that there was at least some money in the city school system, a situation that was to change drastically in a couple of short years. By 1931 there were deep cuts in the school system and almost a fourth of the employees of the city’s system were let go. The twelfth grade was eliminated also.

The 1930 team picture is significant for the presence of a young man in a suit identified as Jack Kiser. He was probably doing his “practice teaching” that year as he had graduated from Lenoir Rhyne College the spring prior. He would go on to be the only Cherryville High School coach to have a winning record and in fact never had a losing season in any sport he coached. He lost only 13 ball games in 15 years with the team.

This picture is significant in that it is the first midget team put together in Cherryville. It also is the first year that the famous Iron Man team of 1934 played together. I have never gotten a clear answer but I think these were 7th and 8th grade kids.

If you look closely at the 1931 team you will see the face of Jack Kiser in uniform on the back row. He apparently, like other coaches of the time, dressed and practiced with the team. It is even possible that he played some games but not real likely at this late date. In the 1920s, it was not uncommon for teachers or coaches or other adults to dress and play to round out squads that did not have enough players to play a game.

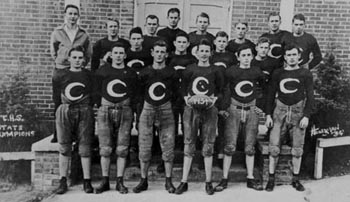

Although the words “state champs” are written on this picture, that is not the case. The 1934 team had a 7-0-3 record and won the championship game for their conference by a score of 6-2. They beat a very good Morganton team, a feat they would not repeat for 14 years. Five players went on to play college football and the team was good enough to be considered to travel to Tamp,a Florida for a “bowl game” against a high school team from there. Notice the C on the front of each player. I am told that these were made from diapers and cut out and sewed on. This was the Great Depression and money was difficult to come by, which also may explain why the team never seriously considered going to Florida.

This was labeled as the John Chavis football team from some time in the 1960s. It may well be true as I am told that most of the black schools in this area played 8 man football. Their equipment looks like it is something left over from the 1940s. It is odd to think about now but the school building you see in the picture still stands and it is no more than a mile from the site of the old Cherryville High School building. It was, in reality, worlds away.

The Combo Offense — One Formation, Two Offenses

January 10th, 2005

Copyright Scholastic Coach & Athletic Director, 2001. Posted by permission of Scholastic Coach & Athletic Director.

By Barry Gibson

Offensive Coordinator

St. Andrews Episcopal School

Ridgeland, MS

In my 23 years of football coaching, I have run just about every kind of offense known to man: power plays, misdirection, options, and wide-open passing schemes, to cite a few.

Innovation can create problems. In my most recent offensive planning, I was looking for something new and exciting, yet old and different. So different that our opponents would see it just once a year — when they played us.

Having always been fascinated by the single wing, I decided to coordinate it with my established shotgun package. I was sure the mixture would have great scoring potential, but since each offense had a significantly different formation that limited what you could do from it. I had to figure out an alignment that would enable us to run either package with maximum power without tipping our hand to the defense.

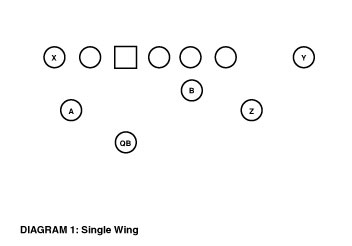

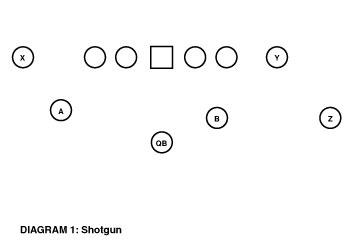

Diagram 1 shows our single wing with our quarterback four and a half yards off the ball, our “A” back upright with his hands on his knees and heels parallel with the quarterback’s insteps, “B” directly behind the right tackle one yard deep, and “Z” a yard outside the unbalanced guard.

Diagram 2 shows our shotgun with the quarterback five yards deep, “B” four yards deep, “A” two yards deep outside of the left tackle and “Z” 17 yards wide.

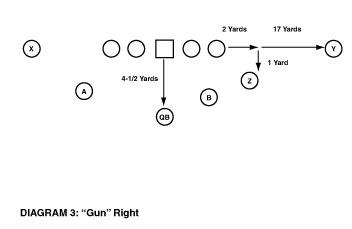

By moving the “Z” receiver to a slot position two yards outside the tackle and one yard deep in the backfield, and moving the “Y” receiver 17 yards out from the ball, we were able to make our shotgun formation look very much like a single wing, except for the unbalanced line.

I call this our “Gun Formation” (Diagram 3).

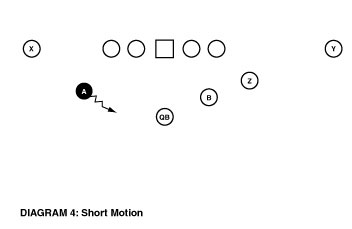

The last piece of the puzzle was putting the “A” back into short motion to his normal alignment in our single wing (Diagram 4). I felt that if I could spread the defense with a new school shotgun formation and throw the football all over the field, while still running the power and misdirection plays from the old-school attack, I would have the best of both worlds!

The accompanying diagrams show the new combo attack at work.

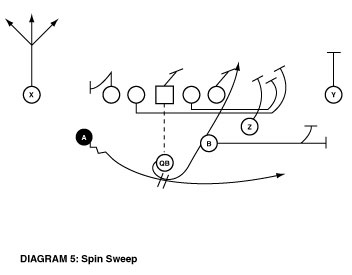

Spin Sweep

The Spin Sweep has always been a big single wing play and it works just as well from our Gun, especially with the quarterback spinning and diving into the off-tackle hole to freeze the linebackers (Diagram 5).

The ball is snapped as the motion man (A) reaches the back side tackle. He then instantly accelerates to top speed — reaching the quarterback’s left hip as the quarterback begins his 360-degree spin. The quarterback hands the ball off with his back turned to the line of scrimmage.

“Z” stalemates the defensive end until the play side guard arrives to help hook or seal him to the inside. The back side guard pulls and seals the most dangerous man to the inside, while “B” (fullback) leads the play to the outside.

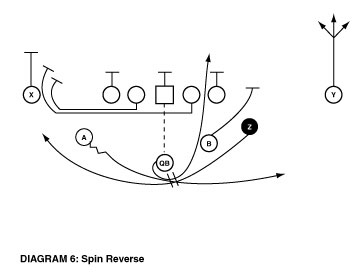

Spin Reverse

In order to slow the defense down and stop them from pursuing hard to stop the Spin Sweep, the formation must have a reverse off of the same action. I believe that there is none better than the Spin Reverse from the old single wing (Diagram 6).

The “A” back does exactly what he did on the Spin Sweep, except that the quarterback now fakes the hand off. With his inside shoulder slightly tucked (to hide the football from the defense), he runs like a scared rabbit toward the sideline.

In one continuous spin, the quarterback fakes to “A”, hands off to “Z”, and then runs into the off-tackle hole with his shoulders down and hands over his stomach — making the defense believe he has the football.

“Z’s” aiming point is the quarterback’s right hip. He must receive the hand off one step inside of “A” and run for daylight out the back side. Both guards will pull for two short jab steps, then whirl back and lead the play for “Z”.

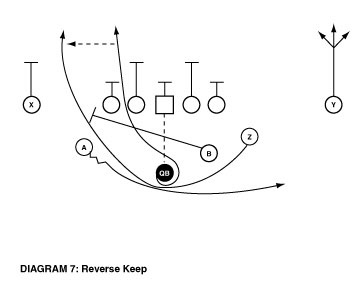

Reverse Keep

Just to give the defense one more thing to think about, we run a Reverse Keep that coordinates beautifully with the Spin Keep and the Spin Reverse. If you want to see the opposing linebackers cross their eyes and develop migraine headaches, watch them try to defend the Reverse Keep (Diagram 7).

This is misdirection at its finest. The quarterback fakes the Spin Reverse and runs for daylight through the back side. I coached him to run away from the near linebacker, but not to get too concerned about him because with all the faking going on, the linebacker isn’t going to know where he’s going most of the time!

We plunge the final dagger in the heart of the defense on this play by having “Z” turn up field, keeping a 5-yard pitch relationship with the quarterback. After clearing the line of scrimmage, the quarterback has the option to pitch to “Z” at any point down the field. We have embarrassed many free safeties who, coming up hard to tackle the quarterback, are left watching the ball being pitched to “Z” at the last moment for an easy walk-in touchdown.

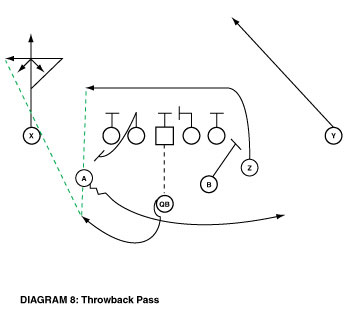

Throwback Pass

Most coaches look at shotgun formations strictly as straight drop-back sets. Very few play-action passes are run from the shotgun, but with the motion that we use with our single wing attack, such passes can be very effective from the “Gun”.

The Throwback Pass (Diagram eight) is one of our favorites, particularly against defensive ends and linebackers who like to quick-read and run hard toward our motion.

The beginning of this play (short motion with “A”) looks identical to the three previous plays and this really keeps the defense guessing and back on its heels. The quarterback will make only a half spin. Then, with his back to the line of scrimmage, he will fake the Spin Sweep to “A”, drive straight back for three steps (again hiding the football from the defense), before bootlegging to the back side ready to run or throw.

The primary receiver, “X”, has three options on his pass route:

1. If the cornerback is playing back or loose, hook inside or outside at 14 yards.

2. If the cornerback is playing up or tight, run a deep “Go” route by him.

3. If the cornerback is playing normal (7-8 yards off), run a sideline route, breaking hard to the inside at 10 yards for three steps before cutting outside and receiving the ball at 14 yards.

“Z” can become a popular secondary receiver by running a 4-5 yard “drag” route across the formation to the bootleg side. “Y” runs through the free safety deep.

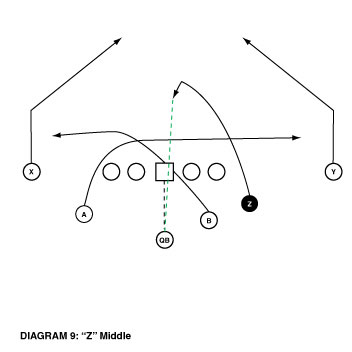

“Z” Middle

The “Z” Middle (Diagram 9) is one of our more successful drop-back passes. Once the defense begins anticipating motion on every play, the ball will be snapped to the quarterback and five receivers will take off quickly. Each will have an opportunity to become a primary target.

“X” and “Y” run post patterns, while “A” and “B” run crossing patterns. We tell our “Z” receiver to find an open spot 10-12 yards down field between the linebackers and then hook up, facing the quarterback.

Well-coached linebackers will drop into zone coverage versus an outside curl zone, leaving a nice little void in the middle. If they decide to run some type of man coverage, they will have to deal with the difficulty of covering our speed guys on crossing routes, which can be a nightmare for most linebackers.

My philosophy on throwing the football has always been: Turn bad guys into cover guys.

Conclusion

I firmly believe that a lot of coaches with all kinds of ideas for their offense have trouble deciding which one to go with. Staying up late at night, struggling over which one to trash and which one to commit to, is a common problem.

Our advice is, stop worrying. With just a little imagination the solution can be very simple: Just Combo It!

Historical Perspective: Jock Sutherland

January 3rd, 2005

Probably no football coach ever constructed a running attack with more precision, power, and sheen than Jock Sutherland. His teams were power teams; the backs ran with fury behind devastating blocking of the unbalanced single wing.

His teams would begin by attacking the flanks and off tackle by sweeps, cutbacks, and reverses. After the defensive line would widen to compensate, Sutherland then would attack inside tackle and up the middle.

In some ways, Sutherland wanted the center to be the best man on his team. “The running game,” he said, “which is, or should be, the better part of football, depends on split-second accuracy and timing from the center. If the ball gets to the runner a tenth of a second too soon — or too late — the running play may be spoiled. So in looking over my talent I pick a man for center who is never rattled or hurried or upset by anything.”

“Sutherland rehearsed every play as if it were an investment in millions,” wrote Tim Cohane. “He would trace the blocking routes with a stick until the pulling linemen ran them to the inch and split second. No other coach came closer to reducing the running game to a pure science.”

As another sportswriter of the time put it, “There was no chi-chi in Sutherland football.” He scorned frills and fancy stuff. The essence of his attack, which was dubbed the Sutherland Scythe, was the unsubtle, power-animated off-tackle play from the single wing he had learned under Pop Warner. He also introduced the double wing formation, with which Warner had experimented when Sutherland was a player. (Warner initially had been dissatisfied with the double wing, but Sutherland recognized possibilities in it which Warner, and others, would later also recognize.)

“Jock had the finest running attack football has known,” wrote Grantland Rice, “and this doesn’t bar Knute Rockne, Lou Little, Percy Haughton, Hurry Up Yost, Howard Jones, Pop Warner, and anyone you can mention. Jock’s great Pitt teams rumbled and blasted out their yardage in the single wing, unbalanced line attack. When Jock had the horses, which was his custom, the Panthers’ attack was something to behold.”

Sutherland was also a genius of defensive football, and his teams were always powerfully arrayed on that side of the ball. Under his command, Pitt shut out its opponents 79 times (55 percent of the time) in 15 seasons.

“His teams were hard to score on, even when you beat him, as Bernie Bierman, with two of the greatest teams in Minnesota history, found out,” Grantland Rice wrote. “As great a coach as Bierman was, he needed the better material to beat Jock. They all needed better material to beat Jock. No one with inferior material ever drew a decision over Scotland’s greatest football son.”

There was a touch of grandeur to Sutherland. Tall, strong, ruggedly handsome, with a formidable jaw and piercing blue eyes, “Jock Sutherland,” wrote Look Magazine’s Tim Cohane, “had a strength of mind, body, and purpose as unshakable and craggy as the hills enveloping his native Coupar Angus.”

He was a commanding, almost majestic figure, an austere man of few words with a reserve not even his players could break down. To those who did not know him, he could seem forbidding. As a result, he earned a few unflattering nicknames over the years, including “the Great Stone Face” and the “Dour Scot.”

“But in his relaxed hours,” wrote New York sportswriter Joe Williams, “which were not infrequent, there could not have been a more companionable man. His soft, pleasing voice rolled with the thistle of his native Scotland. He had wit and wisdom and a certain grace.”

None of his players ever dreamed of addressing Sutherland, either during their playing days or in later years, as anything but “Doctor.” The fierce devotion and respect they had for him lasted a lifetime.

Sutherland was a stern taskmaster. He sometimes would set the pace for his players by striding up the long steep hill leading to Pitt Stadium and insisting that his players do the same. He admonished those who hitched a ride from a passing car, in his Scottish burr, to “get off that curr.” The penalty for those he caught riding up the hill: extra laps.

Sutherland never criticized a player publicly, and was privately considerate of them, especially in bad times. He was their champion, who fought tirelessly for them, who encouraged them and who rejoiced proudly in every advance each made both during their college days and long afterward.

“Although he was a driver, an exacting teacher, a stern disciplinarian, Sutherland’s players knew he was interested in their futures,” Cohane wrote. “He steered many of them into the professions. They knew also that he was inwardly warm, sympathetic to their problems, always their defender. When they lost, they had a feeling they had betrayed him.”

That didn’t happen often. In his 15 years as coach at Pitt, the Panthers compiled a brilliant 111-20-12 record. Four times, playing a rugged schedule, his teams were undefeated. Five times they were invited to the Rose Bowl. Five times they were recognized as national champions.

Pitt played Notre Dame six times from 1932-1937, and the Panthers claimed victory five times. After a decisive 21-6 loss to Pitt in 1937, Irish Coach Elmer Layden decided “no mas” and reasoned Notre Dame would be better off not playing the Panthers. “I’m through with Pittsburgh,” Layden said. “We haven’t got a chance. They not only knock our ears back, we are no good the next week. I’m calling off the Pittsburgh series.”

Notre Dame was just one of the powerful teams Pitt faced in those years. Sutherland insisted on playing the most formidable schedule possible, and as a result he generally resisted pointing his team for any one game. For the most part, as far as the Pitt players were concerned, one opponent was just like another. They were taught to have a high regard for all of their opponents and to go — as Jock put it — helter-skelter from whistle-to-whistle.

He managed to keep his players at a high level all season by coaching them in a calm, professional manner. Locker room histrionics had no place in his system. There were no known “Win one for the Gipper” pep talks from Sutherland.

Before a game he would tell his players what he wanted them to do. At halftime he would inform them if they had failed to do that. If they were losing at halftime, he wouldn’t whip them into a fury by screaming at them, pleading with them, or shedding tears over the calamity about to befall the old alma mater.

Consequently, Sutherland’s teams didn’t rush out of the locker room in “a lather”. He simply didn’t believe in furious football — the fighting, crying, hysterical kind of football. He wanted his players to fight hard all the way. But he didn’t want them to play with their heads whirling and tears of rage in their eyes. That wasn’t his kind of football. His teams were known for their slamming, hammering, power football. But the force they exerted was a precision that called for clear, cold thinking rather than emotion.

Sutherland, a native of Scotland who, according to legend, played in the first football game he ever saw, is Panther football’s all-time crown jewel. Both as an All-America guard for Pittsburgh during a brilliant four-year playing career under Pop Warner, and later as a Hall of Fame coach whose dominating teams were knighted as national champions five times, he set impeccable standards of excellence at Pitt.

Sutherland became a larger-than-life figure not only at Pitt but throughout the college football world. When he died unexpectedly of a brain tumor in 1948, the city of Pittsburgh and the sporting world mourned the loss of one of the truly great men in sports.

“Jock, above all, was a leader,” said the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in an editorial upon his death. “This impressed you at once on first meeting him. Character, restraint and sincerity were written in his bearing. “There is nothing anybody can say about the passing of Jock Sutherland that isn’t felt in the heart of every man and woman in Pittsburgh. In any list of the district’s assets, he was close to the top.”

Johnny Sutherland was one of seven children born to Mary Burns Sutherland, a descendant of the poet, Robert Burns. When his father, Archibald, suffered a fatal internal rupture trying to save the life of a fellow worker pinned under a fallen girder, Mary Sutherland sent young Johnny to America to join relatives here and escape from a life of certain poverty in Scotland.

When he arrived in America, the 16-year-old Sutherland was determined to educate himself and get ahead. After working his way through several prep schools, including one job as a night policeman in the Pittsburgh suburb of Sewickley, he entered Pitt’s School of Dentistry in 1914.

During his early years in America, Sutherland focused his sturdy, 6-4, 210-pound frame on soccer, the game most popular in his native Scotland. But when Joe Duff, the Pitt football coach in 1914, got one look at this tall, strapping Scot, he convinced him to try his hand at football.

By the second game of the season, “Jock,” as he came to be known, became a starting guard. He flourished at the game. Like a bridge player who understands the system behind the play, Sutherland sensed the reasons for the moves on the gridiron, and he developed into one of the greatest guards in Pitt history. He became an All-American under Pop Warner, who succeeded Duff as head coach in 1915.

During his four years as a player, Sutherland only tasted defeat once; the Panthers were undefeated in his final three seasons, and were recognized as national champions in 1915 and 1916. Sutherland also had a perfect record, as both a player and a coach, against Penn State. The taste he acquired for victory as a player would carry over into his brilliant coaching career.

After a tour in the Army, during which he coached several camp teams, he accepted an offer in 1919 to become the head coach at Lafayette College. He spent five years at Lafayette, producing an Eastern championship team in 1921 and defeating Pitt twice in a row. In 1999, 97-year-old Joe Marhefka, a backup halfback on that 1921 team, recalled that the main thing most Lafayette players learned in that training camp was how much they wanted it to end. Marhefka recalls that Sutherland was a “very strict fellow who wasn’t very friendly at all.”

When Pop Warner left Pitt for Stanford in 1924, Sutherland returned to his alma mater as head coach, where he remained through the 1938 season. During those 15 years he won five national titles (1929, 1931, 1934, 1936, 1937) and took his teams to four Rose Bowls. He left Pittsburgh in 1939 to coach the NFL’s Brooklyn Dodgers in 1940 and 1941. But there were those who said he was never happy there. The war came and he joined the Navy. Then in 1946 he accepted the head coaching job with the Steelers. He was home again in Pittsburgh.

“It’s strange,” Art Rooney, legendary owner of the Steelers, recalled. “But shortly after we announced the signing of Jock Sutherland, we started to sell tickets like never before. He was a magic name in Pittsburgh. It was right after the war and no one, not even Sutherland, knew what players we would have, but the Pittsburgh fans had faith in this coach.”

The news took the city by storm. Before the Steelers played a single game in 1946, tickets to games at Forbes Field were totally sold out through 1949.

Sutherland’s approach was all business. Before Paul Brown had ever heard of playbooks, Sutherland had used them. Sutherland made extensive use of game films and introduced the Steelers to the concept of classroom sessions for players.

And for Art Rooney, who really hadn’t known Jock before he hired him, was practically in awe of the man. Rooney gave Sutherland free hand in the operation of the Steelers. Rooney learned more about the administration of the game in those two years with Sutherland than he had ever learned in his life.

After Sutherland’s sudden death in the spring of 1948, Jock’s assistant and disciple, John Michelosen, was hired as his successor. Michelosen stuck with the single wing for four seasons despite the fact that every pro team and almost every major college had abandoned it for the T-Formation. Following the 1951 season Michelosen was let go and the Steelers put the single wing to rest.

George Matthews

Deer Lakes Youth Football

Sources:

2003 Pitt Football Media Guide

The Morning Call Inc., Allentown, PA - 4/4/99

The Pittsburgh Steelers – A Pictorial History By Pat Livingston, published 1980 Jordan & Company.