Triple Wing

November 25th, 2007

12 Feb 1966

Dear Bill:

Am very sorry that I have not gotten some material to you on the triple wing back as I promised. We have been getting this office transferred to Bill Murray at Duke and I haven’t had a chance to go into the archives and dig out the materials before going on an extended foreign trip in a few weeks.

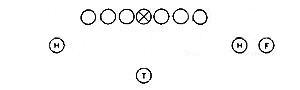

The best I can do now is to give you a short resume and development of it and how it evolved. Also the formation and the variations that I used. It never had a good test. We hit a peak with it in 1932 — an 8-1 season — after defeating Princeton 3 years in a row on their own field with it.

I will jot down some illustrations on the enclosed pages.

Sincerely Yours,

D.O. McLaughry

P.S. The enclosed will give you a rough idea but when I get back I will dig out the orderly material that I know is somewhere.

The idea grew out of the close double wing, we were using it with a balanced line but it would be nearly the same from the unbalanced line. The first play used with a third wing back was the final game in 1928 vs. Colgate. I took the inside blocking back and set him outside the def. left end to block him in on a double reverse that finished up around him. It went from the 16 yd line for a touch down, the first time it was used.

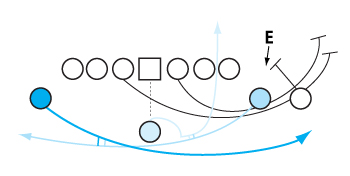

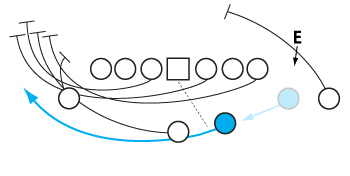

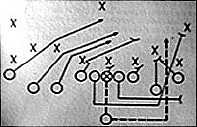

The reverses off tackle went as follows: the front running guard took the place of the inside blocking back on most all inside blocking.

The fake reverse inside tackle was very strong. Sometimes we pulled the guards the opposite way on it.

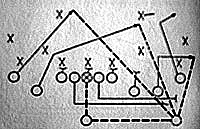

#1 Back always faked blocking the end on all inside plays and forward passes. He set left as well as right.

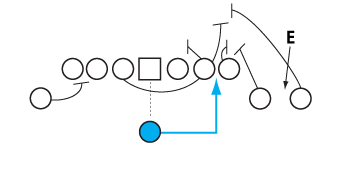

The passes were thrown by the #3 back dropping back or by #4 on reverses. #3 would rise up with the ball, fake a pass and run up the middle. This was our draw play.

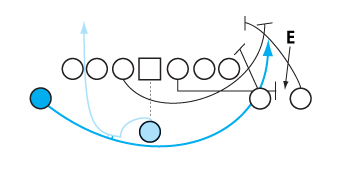

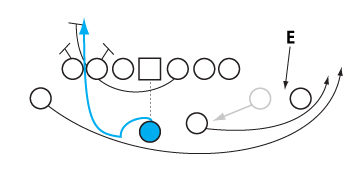

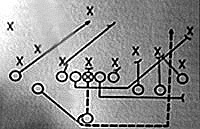

When the defenses over shifted toward the “setter” we had the following variation — particularly end runs to the short side.

As an illustration the following end run went 70 yards for a touchdown on the first play at Princeton in 1931.

Shifted back with a cross over step and a skip as he landed the ball was passed

Cross over step, then Rt. always facing the line

Fake reverse after the rt. wing back had shifted back.

We hit every hole 2 or 3 different ways, both running from the straight triple wing and with the one man shift.

It is necessary to have a good blocker and faker in the #1 spot, two good running guards.

The strength and advantages:

1. Blocking angles on all defensive players except short side end.

2. Five (5) eligible receivers either on or one yd back from the line of scrimmage.

3. Reverses — single and double very strong — build up the fake reverse with guard going opposite way.

4. Quick passes over the short middle to the #1 man, after the fakes at def. end — very good.

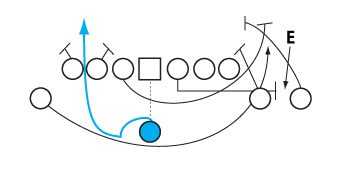

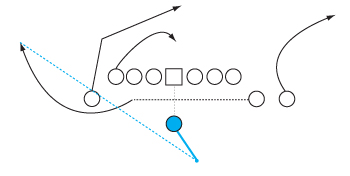

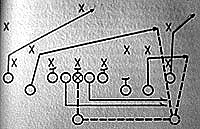

Following pass defeated Holy Cross in 1932 late in game.

Direct Snap Note: To read more about D.O. McLaughry, click here.

Dutch Meyer’s TCU Spread

November 12th, 2007

OLD SCHOOL FOOTBALL NEWSLETTER

2007 – ISSUE 4 – By Hugh Wyatt – www.coachwyatt.com

Before you start firing off e-mails denouncing me for breaking my pledge to write about OLD SCHOOL FOOTBALL by writing about something with the word “SPREAD” in it… Relax. Bear with me.

The book shown above may look as if it’s the handbook for everything you dislike about where the game of football has gone since holding was virtually legalized, but it really is “Old School Football” - it’s more than 50 years old. A look inside it is enough to see that the author was giving us a peek at the future o the game.

It’s the work of long-time TCU coach Dutch Meyer, and it was published in 1952, following his retirement after 19 years as head coach of the Horned Frogs.

During those years, Dutch Meyer did as much as any man in football history to advance the passing game as a staple part of the offense and not simply a diversion, and in doing so, lay the groundwork for much of what we see in today’s modern “shotgun” offenses.

His offense and his philosophy were considered radical during his time, a time when offenses consisted mostly of the single-wing or full-house T-formation attacks that we see on the grainy old films of those days. But if you were to show people nowadays a few clips of what Dutch Meyer was doing more than 50 years ago, other than the helmets, it wouldn’t look “old school” at all.

They’d look at it and say, “Shotgun,” of course. But they’d be wrong. That term, given to a direct-snap attack used by the San Francisco 49ers, dates back only to 1960, well after Coach Meyer retired.

Nowadays, of course, any offense that requires a direct snap is automatically and generically called a “shotgun”, but in the mid-thirties, when Dutch Meyer took over at TCU, every offense was a direct-snap offense.

Nowadays, too, fans and announcers look at the guy to whom the ball is snapped in the shotgun and call him the “quarterback.”

But Dutch Meyer didn’t. Dutch Meyer called him the “tailback.” What else would anybody who knew anything at all about football back then have called that guy? Single Wing, Double Wing, Spread formation, or any other offense run by the major teams in the 1930s – that guy back there who caught the snap on 90 per cent of the plays was the tailback.

Unfortunately, that name has been misapplied for so long to the deep back (the “I-back”) in the I-formation that today’s TV people look at the man standing back there waiting for the snap and

call him the quarterback, leading to such hysterical – and absurd - observations as “they’ve got a wide receiver lined up at quarterback!”

In the old single wing, there was a quarterback. He, and not the coach, called the plays. The rules at the time prohibited coaching from the sideline, but limits on substitution would have

made shuttling plays in and out impractical, anyhow. And just to make sure no hanky-panky went on, until 1941, a substitute was forbidden from communicating with teammates until he’d

been in for one play (unless he was substituting for the quarterback).

So the single-wing quarterback was a true “field general.” But unlike today’s quarterbacks, he seldom handled the ball. After calling the play and calling the signals, his main job was to

block, and so he was commonly known as the “blocking back.”

Dutch Meyer didn’t have a blocking back in his spread offense, because his offense derived from Pop Warner’s double-wing formation, which didn’t have a blocking back, either. He didn’t

have a position named “quarterback.” Dutch Meyer’s tailback called the plays - and he handled the ball on nearly every play.

Besides his tailback, Coach Meyer had a fullback and two halfbacks, deployed most of the time in such a way that, with both of his ends split, he had three slot receivers. He was running “five

wides” long before most of today’s advocates of the wide-open passing game were born!

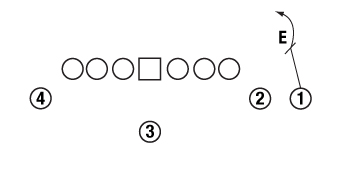

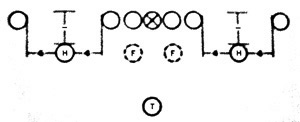

DUTCH MEYER’S “TRIPLE WING”

DUTCH MEYER’S “NORMAL” FORMATION

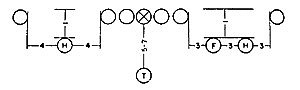

DUTCH MEYER’S SPREAD

(Note that in his “normal” formation, Coach Meyer aligned his fullback in the backfield to one side or the other in order for him to be able to take a direct snap.)

THE TCU SPREAD - FROM A FILM CLIP

That his spread offense worked is beyond question. In his 19 years at TCU, from 1934 through 1952, Dutch Meyer’s record was 109-79-13. At a time when bowls were few, his TCU teams played in six major bowl games – 3 Cotton Bowls, 2 Sugar Bowls and one 1 Orange Bowl.

His 1938, 1944 and 1951 teams won Southwest Conference championships, and his 1938 team, which finished 11-0 and outscored opponents 269-60, was national champion.

It could be said that he was blessed with two great tailbacks in Sammy Baugh and Davey O’Brien, but it is only fair to give him the credit for making the most of their great talent.

One of his first acts upon taking the head coaching job at TCU – he had been baseball coach and an assistant football coach for the previous eight years - was installing Baugh, whom he’d recruited as a baseball player, as his starting tailback.

To take advantage of Baugh’s throwing ability, Meyer opened up his classic double-tight, double-wing direct snap attack by splitting his ends and widening his wingbacks more than usual. With Baugh throwing from what became known as the “Meyer spread,” TCU compiled a 27-7-2 record over Baugh’s three seasons.

When Baugh graduated and went on to NFL stardom, Meyer replaced him with little (5-7, 150) Davey O’Brien. Although perhaps not as great a passer as Baugh, O’Brien was a better runner, and with O’Brien at tailback, TCU’s 1938 team was named national champions. For his performance, O’Brien won the Heisman Trophy in just the fourth year of its existence.

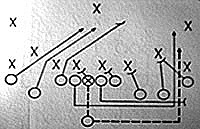

Above, Coach Meyer’s tailback sweep to the trips side is shown against three different defenses. Although Dutch Meyer referred to the defenses of his day by other names, it isn’t hard to look at the defenses in some of his diagrams and see that the defensive coaches of the time anticipated some of the things that today’s defensive coordinators are doing against today’s spread offenses.

Above is the tailback sweep shown to the short side – away from “trips” - and below that (sorry to disappoint all the guys who think they’ve invented various “spin” offenses and the like) is the TCU halfback sweep.

Shown above is the TCU “Run-Pass,” designed, as Coach Meyer said, “to start and appear exactly like the sweep.”

One concession to the football of his time was Coach Meyer’s obvious reliance on athletic guards. It isn’t likely that many of today’s highly-specialized offensive linemen, built primarily for pass protection and zone blocking, would have the athletic ability – or the stamina - to play for Dutch Meyer.

In an interview Sammy Baugh gave to the Washington Post, years after he’d gone on to a Hall of Fame NFL career with the Redskins, one can even see a little of Dutch Meyer’s influence on today’s West Coast Offense:

“Dutch Meyer taught us. All the coaches I had in the pros, I didn’t learn a damn thing from any of `em compared with what Dutch Meyer taught me. He taught the short pass. The first day we go into a room and he has three S’s up on a blackboard; nobody knew what that meant. Then he gives us a little talk and he says, `This is our passing game.’ He goes up to the blackboard and he writes three words that complete the S’s: `Short, Sure and Safe.’ That was his philosophy — the short pass. “Everybody loved to throw the long pass. But the point Dutch Meyer made was, `Look at what the short pass can do for you.’ You could throw it for seven yards on first down, then run a play or two for a first down, do it all over again and control the ball. That way you could beat a better team.”

ONE FINAL WORD FROM COACH MEYER, FOR THOSE WHO MIGHT BE TEMPTED TO DABBLE (I believe some readers may have heard me say this, oh, one or two thousand times with regard to the Double-Wing):

“Just one word of warning. Some teams have tried the spread as a surprise element – putting on only a few plays and passes in the hope of catching an opponent unaware and unprepared. And it has worked fairly well at times, too. But to get the full benefit of the spread, it must be installed as a principal formation and must be developed so that advantage can be taken of any weakness developed in the defense.

Some teams, stopped cold on the few maneuvers given off a spread setup, have given up in disgust and returned to their “main stuff.” This may have happened even though the few spread plays used disclosed some glaring weakness in the defense encountered. Sometimes the failure is due to the fact that the blockers had not worked enough with the idea to master the flexibility of assignments.

To be really successful, a spread team must be equipped with enough weapons to hit every weakness and the players and the coaches must study the setup thoroughly.”

Copyright 2007 Hugh Wyatt. All rights reserved. www.coachwyatt.com

To get on the mailing list for my free newsletter - e-mail me your name, location and e-mail address at: oldschoolfootball at mac dot com (your information will never be given out to anyone else)