Sigourney-Keota, IA Shift

March 20th, 2006

Like most coaches, I am always looking for an edge, something to give us an advantage over the competition. That was one of the main reasons we began to run the single wing offense in 1987. At that time we were the only school in Iowa using the offense and there are still only three or four of us in the state. Our offense has evolved throughout the 19 years and we have employed several “wrinkles” to stay ahead of our opponents, from putting a quarterback under center and snapping through his legs, (like Biggie Munn and the Michigan State system), to using a double wing look with motion, to two spinbacks both spinning at the same time, to our recent use of the quick shift to a predetermined formation from a pre-shift set.

The state of Iowa has several “T” teams that run a quick-huddle offense. They are always tough to prepare for because their offense is different from what you normally see. You must practice against it and take practice time to teach your scout team to run it. Of course people have the same practice issues when facing the single wing, particularly with the spinback. We want to be as big a pain for our opponents as possible and combining the quick-shift with the single wing has to be difficult to practice against especially at playoff time when there is less than a week to prepare between games.

To begin with our shift involves a cluster of linemen behind the center, 1-2 yards off the ball ready to “jump” on command into their prescribed alignment as determined by the huddle call. There are a number of reasons for the shift other than the fact that we think it looks cool.

Rationale for the Shift

1. Prevents or makes it much more difficult for our opponents to flip-flop their defensive personnel. Many teams were playing a strong side and quick side that would flip-flop with the strength of our formations. They are still able to flip linebackers and defensive backs, but we have pretty much eliminated the moving of defensive tackle and ends from side to side.

2. To gain a numerical advantage. We shift to our basic unbalanced line, to balanced lines, to eight-man lines and sometimes even nine man lines. We shift the strength of the line in one direction while the backfield shifts independently into any one of many backfield sets. We feel that it is much easier to get an advantage on our opponent since the attention of the defense is on the movement of the line, particularly the two tackles, which not only diverts the attention of the defense but also makes is easier for our smaller backs to move behind the wall of linemen into their positions without being identified easily. We can move our backs into various overload formations to gain an advantage at the point of attack and snap the ball before the defense can adjust. This is all derived from the basic philosophy of the Notre Dame Box.

3. To set up opponents. Most of the time we are shifting into our base formations. Last year we seldom used our special formations during the regular season because we wanted to save them for the big games. We are able to establish tendencies that we can break when we need a big play.

4. Control the tempo of a game.

As with anything when there are strengths there are also weaknesses.

1. Penalties. This past season we had four precedural penalties in 13 games. Three were committed by our ends not being set (two on the split ends) and the other penalty was on the quarterback anticipating his own snap count and getting in a hurry and leaning. We also had eleven seniors, seven of them three-year starters. That certainly helped keep the penalties down, but we have never had many. We practice jumping into their stances and freezing from the first day of camp and the penalties have never been a concern of using the shift.

2. Loss of the use of audibles. With the quick-shift and go offense, it is much harder to use audibles. We were able to use some audibles this past season by alerting the team in the huddle that we were running a “check” play. To be honest the defense usually jumped because the check call was the equivalent of going on two. Our cadence is “Down” (which moves the team from pre-shift to their formation alignments) — “Go” — “Sethit”. We always snap the ball on the “Sethit” command unless we are using “Go”, “On Two” or “Check”.

The pre-shift alignment of the linemen can be configured in many different ways. We have used several over the years, mostly accommodating the different sizes of our linemen and their agility to “jump” to the various alignments. We use the term “jump” because we want to emphasize moving quickly to their spots. Usually they take no more than three to four quick steps and they are in their stances. Their last two steps should land then into their stances with correct spacing because once they put their hand on the ground we do not allow any movement of their feet. Obviously this takes a lot of practice but it can be accomplished without too much trouble for just about any lineman.

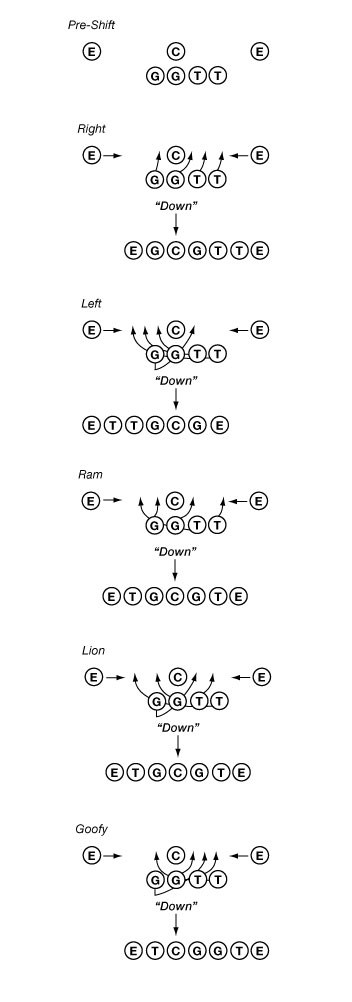

Here is the pre-shift alignment we used last season for our offensive line.

Our center and ends leave the huddle at the same time and go to the line of scrimmage with the ends on their appropriate sides. We use enough slot formations that our opponents do not get much of a tendency by the alignment of the strong and and quick end. We also use “switch” calls which switch the ends if the defense is putting a good defender to the side of our tight end all the time.

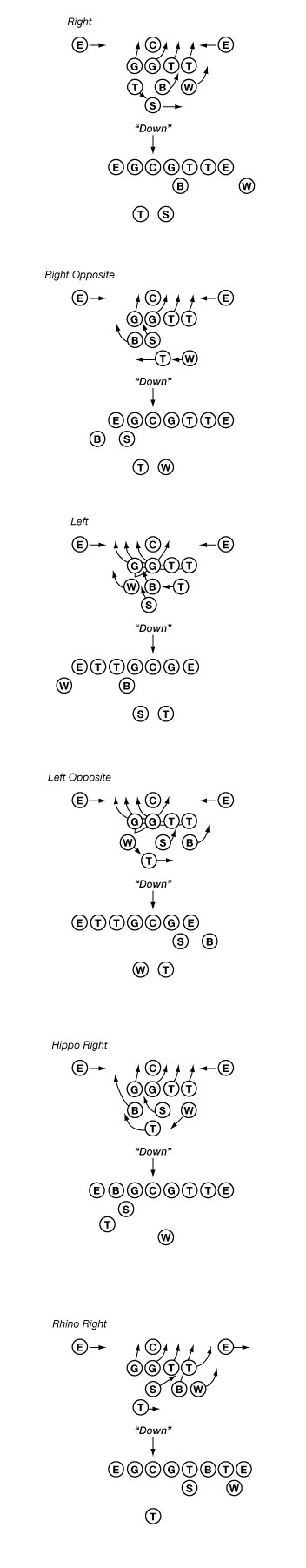

Here are examples of several of our base formations and how we move to them prom pre-shift alignments.

Your imagination is the only limit to the possibilities of formations and shifting. Please feel free to contact me if you have questions.

Bob Howard

Heach Coach

Sigourney-Keota, IA

howardb at aea15.k12.ia.us

Ken Keuffel

March 3rd, 2006

With the passing of Ken Keuffel, we have lost a major link to our football heritage. Coach Keuffel, for more than 20 years the head football coach at the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey and for another 6 years the head coach at Wabash College, died last Sunday in Princeton, N.J. at the age of 82.

As coach, clinician and author, Coach Keuffel was a leading bearer of the single wing torch long after the offense had all but disappeared from the game, writing two books on the offense, “Simplified Single Wing Football,” published in 1964, and “Winning Single Wing Football“, published in 2004, that are must-reading for anyone interested in running the offense or just learning more about its inner workings.

Coach Keuffel played at Princeton University for Coach Charlie Caldwell, who like most college coaches at the time ran one form or another of the single wing. (The single wing was last used in the National Football League by Coach Jock Sutherland of the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1947, and last used at the major college level - by Princeton - in 1967.)

Although the single wing has disappeared from the colleges, it did hang on at widely -scattered high schools, and thanks largely to the Internet, it has made something of a comeback in high school and youth football. (Evidences of it can also be seen in today’s “modern” shotgun offenses.

Coach Keuffel felt its near-extinction provided him with several advantages. “One of the big ones,” he told the New York Times in 1973, “is that rival teams find it difficult to prepare for us. They aren’t familiar with the single wing.”

A native of Montclair, N.J., he started his college career in 1943 as a Princeton fullback, then left for service in the Army Air Corps. Returning to Princeton after the war, he was a single-wing quarterback (blocking back) and place-kicker.

In 1947, his 29-yard field goal with a minute to play gave Princeton a shocking 17-14 upset victory against Pennsylvania, then ranked third in the nation, and Philadelphia mounted police had to be called on to prevent a near riot that atrted whenwhen Princeton fans among the 72,000 spectators tried to tear down the goal posts, and angry Penn fans opposed them. (My high school coach, Ed Lawless, played quarterback on that Penn team.)

Following graduaton with a degree in English, he coached the Penn freshmen under another legendary Single-Wing coach, George Munger, while earning a doctorate in English literature from Pennsylvania.

In 1954 he became a teacher and an assistant coach at Lawrenceville, and became the head coach at Lawrenceville in 1956. Following the 1960 season, he left to become head coach at Wabash, , but in 1967 he returned to Lawrenceville, where he coached until his first retirement in 1982.

Coach Keuffel was coaxed back into coaching a few years later, and stayed on through 2000, when he finally retired at age 76. And always, although he made many alterations along the way, he coached the unbalanced single wing of Princeton and Penn.

Coach Keuffel was generous with his help and advice. He was a highly refined, a gentleman of the old school who saw himself as a teacher first and a coach second.

His ability to write served him well when it came time to publish his books. I once kidded him about devoting an entire chapter in his first book to the subject of stopping the single wing. “Why?” I asked him.

“I wanted to sell more books!” he told me, laughing.

He was very proud of the fact that in most years at Lawrenceville, a prestigious all-boys prep school, roughly half of its enrollment of 600 were playing either varsity, junior varsity or club football.

Copyright 2006 Hugh Wyatt. All rights reserved. www.coachwyatt.com