Running Pass Plays

February 28th, 2005

Dr. Ken Keuffel

Legendary Single Wing Football Coach

Author of “Winning Single Wing Football”

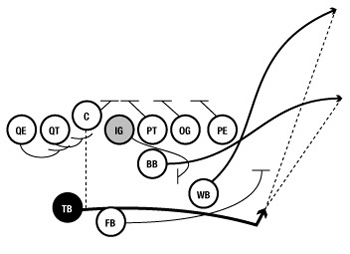

The running pass by the tailback is one of the most potent weapons in the single wing arsenal. We have executed the running pass in two similar ways. The last digit of each play is 9, indicating that each can end up wide to the strongside as a run. Blocking assignments on both passes are the same for all interior linemen and for the fullback, who blocks the end man on the line. The plays are similar in design and operate on similar principles. The difference comes in who the two strongside receivers are.

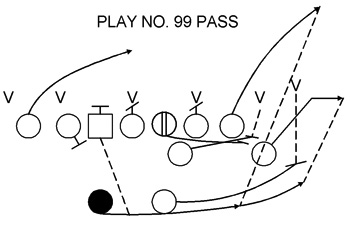

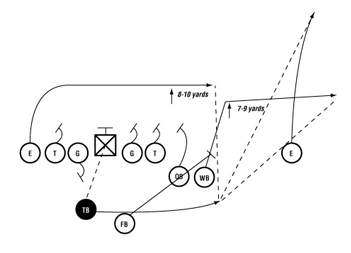

On Play No. 79 Pass, the pattern we have used most, the wingback is a deep receiver running a banana course, and the blocking back is a shallow underneath receiver running in the flat at about 3 yards’ depth. On Play No. 99 Pass, the No. 8 end runs a deep banana route, and the wingback runs a sprintout course at about 3 yards’ depth with the blocking back blocking the second man in.

There are good reasons for having two such similar plays. Sometimes we have a real difference in the receiving ability of players. For example, the blocking back may be a poor receiver and we may want to use the wingback in the flat pattern. Also when we line up the wingback on the weakside, we still have a deep outside threat from the No. 8 end with Play No. 99 Pass. Finally, we have found it convenient to designate variations of the running pass by 99 as I’ll show in the next part of this chapter.

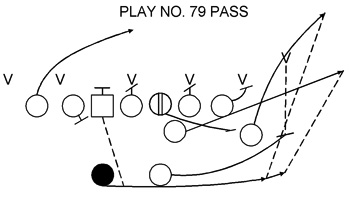

Play No. 79 Pass

Now I’ll discuss Play No. 79 Pass in more detail. From near position (behind the center) the tailback takes a 4 (lead) center and runs under control to the strongside while setting the ball in his hands to pass. We want him to look for his receivers early. Ideally he should be ready to throw by the time he is behind the wingback’s original area. The wing must run his banana course from the start. He must not run downfield and then veer to the outside or the safety can rotate over and pick him up while the halfback moves up to cover underneath. If the wing is open, the tail throws him a high, soft pass over his outside shoulder. The blocking back runs at the defensive end and then slides into the flat.

Both the wing and the blocking back are effective receivers on this play, and both are in the tailback’s line of vision. The tail can look to throw to the wing first and, if he’s covered, throw to the blocking back. Or on what we call a “79 Run It,” he can expect to run the ball unless he’s rushed, in which case he throws to the blocking back. We practice these possibilities and thus can easily adapt to the way the defense is playing. As I said earlier, I never want the passer to have more than one option.

Here are the other assignments for Play No. 79 Pass. The No. 8 end blocks any man in his area, usually the second man in. No. 7 blocks anyone from his outside seam to head-on No. 6. The No. 6 lineman pulls with some depth and blocks where needed. However, he must not pull against packed defenses but instead must block the man on him. The reason: No. 7 cannot block men on both himself and No. 6. The No. 5 lineman blocks anyone from his outside seam to head up. The center blocks any man on him. The No. 3 lineman blocks anyone on him or (if no man on him) the first lineman to the weakside. The No. 2 end runs through the short middle zone as a receiver.

For many years we used a three-man pattern on Play No. 79 Pass with the No. 8 end going straight downfield about 8 yards and then cutting sharply to the outside. We sometimes had success in hitting this receiver. In one Lawrenceville School game in 1971, the No. 8 end caught four passes for good yardage on this play, but we don’t usually have that kind of player at tight end. In recent years we have had the No. 8 end block any man in his area. This gives us maximum protection and allows the tailback to focus in a progression on the wingback deep and the blocking back in the shallow flat. With practice, a schoolboy passer can handle this simplified task.

Jeff Bayerl

Freshman Head Coach

Menominee, MI

The biggest hurdle that needs to be cleared, in my opinion, is the coaches ability to get the tailback to make the decision to run or pass at the right time. We rep it this way. I and another coach will pre-determine who’s going to cover the wingback, who’s going to rush, or both stay back in coverage, one take the wingback one take the quarterback. Make the tailback make his decision quickly and not be indecisive.

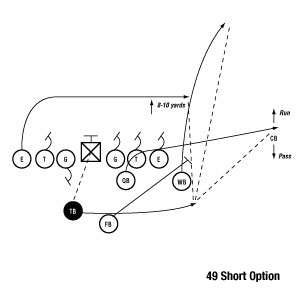

The other thing that always gets forgotten is the 49 Short Option drill. This drill is essential for the tailback to throw on the run. To make this a precise throw the tailback needs to know that while he’s moving his target is also moving. Instead of leading the receiver he needs to throw directly at the receiver as they are both moving at the same speed. This coaching point is critical and is generally the reason that the play fails. Most coaches don’t teach this and therefore give up on the play claiming it doesn’t work, or the completion percentage isn’t what they’d like it to be.

Eric Strutz

Youth Football Coach

Stateline Comets, Richmond IL

We had great success with this play in 2001 and 2002 in part because we ran the sweep often and we ran the sweep well. This usually causes a rotation of the secondary as the strongside corner steps up to force as soon as he reads sweep. We position the wingback in tight to the formation and have him run right off the tail of the power end into his pattern and we have the blocking back take his first few steps more or less straight down the line of scrimmage. This action not only sells the run, but also conceals the first step or two of the receivers from the defense.

The wingback’s path is at one o’clock for 7 yards and then he breaks at one-to-two o’clock to run away from the rotating safety. He is often able to get completely behind the defense very quickly. The blocking back’s path is at three o’clock for a 3-4 steps, bending at 10 o’clock for 3-4 steps to cross the line of scrimmage and then back at two o’clock to run away from the coverage. The tailback sells sweep, keeping the ball hidden on his right hip. He gets some depth, running at about 4 o’clock for 4 or 5 steps before looking deep first, then to the blocking back. In 2 seasons, we completed this pass to the wingback 10 times for 322 yards and 6 touchdowns. We completed it to the blocking back 7 times for 75 yards and 2 touchdowns. We threw it incomplete 10 times and we threw 2 interceptions, neither of which was returned.

Adam Wesoloski

Youth Football Coach

Green Bay, WI

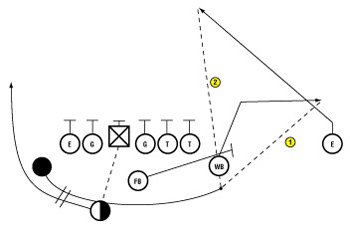

In 2000 our team ran a direct snap double wing offense. We were loaded with talented wingbacks. Our best passers were our left wingbacks so we set up our running pass play where we used our basic wingback reverse backfield action but with pass routes. We coached the wingbacks to recognize the open receiver quickly and get them the ball or otherwise keep the football and run. At our age level, 8-10 year olds, they have a more difficult time seeing the play develop so they ended up running the football more often than pass. I preferred this decision making since it prevents uncertainty and lowers the risk for turnover.

Snap & Go!

Adam

adam_wesoloski at yahoo.com

West Coast Single Wing Clinic

February 21st, 2005

When

Saturday May 7th

Where

Liberty Christian School

(714) 842-5992

7661 Warner Ave,

Huntington Beach, CA 92647

Contact: Bert Ford

Cost

Free

Schedule

8 AM - 5:30 PM

5 hour and half sessions

8 AM - 9 AM registration

Schedule

9:00-10:00 AM Bert Ford: “The Wedge”

10:00-11:00 AM Ted Seay: “Supplementing the Core Single Wing with Other Direct Snap Formations — A Formation & TCU Spread

11:00-12:00 Noon Tom Davis: “Single Wing in a Week”

12:00-1:00 PM (Lunch)

1:00-2:00 PM Bruce Eien: “The Fat Formation”

2:00-3:00 PM Ty Colbert: “Achieving Competitive Excellence”

3:00-4:00 PM Richard “Air” Flores:”Installing the Single Wing for First Time Coaches”

4:00-5:00 PM Harold Strauss “Merging the Double Wing with the Single Wing”

Any questions e-mail Coach Bruce Eien at [email protected]

Wildcat Snap

February 14th, 2005

Coach Wyatt’s latest coaching tip is very interesting.

Coach, How does the center in the Wildcat offensive set know who to snap the ball to? Say Wildcat Rip 88 Power. Do you have a key word or something that tells the center which side to snap the ball to? We will be running this in our youth program this year.

Coach, this may sound strange to you, but he doesn’t know who to snap the ball to. All we want him to worry about is the snap count and his block. We don’t want him to have a third thing to have to deal with.

We used to have the players tell the center which one to snap it to, but not any more. Not since I came across some old clinic notes from a now-retired single-wing coach named Jerry Carle, from Colorado College. He had a formation similar to my Wildcat, in which he had two single-wing tailbacks, side by side, directly back of center, except that his guys were a few yards deeper. He told his center to snap it straight back, between the two of them, and it was their responsibility to know who was getting the ball.

I figured that as close as our guys were and as short as our snap was, that would work just as well for us, and sure enough, it did. So that is what I teach now and it works great. As always, you have to constantly drill the idea of “soft and low” into the center’s head, but you have to do that in any case if you are going to run the Wildcat.

Good luck. You will enjoy it.

Copyright 2005 Hugh Wyatt. All rights reserved. www.coachwyatt.com

Video of Coach Wyatt’s Wildcat Snap is here.

Modern Single Wing Football

February 7th, 2005

by Charles W. Caldwell, Jr.,

Head Coach, Princeton University

J.B. Lippincott, 1951

Excerpt from Chapter 1 — The Human Equation (pages 19-21)

The longer I coach, the more I work with boys, the more clearly I understand that the seemingly call incidents — often chance happenings, — are largely responsible for those decisions that shape an individual’s career. In my own case, it took a great team, and the master coach of them all, Knute Rockne, to convince me that football was for me, that coaching was a profession requiring the same kind of intense study and lifelong devotion demanded of teachers, lawyers, and even doctors.

No, I never played for Rockne. I played against him, or against his 1924 team that included the celebrated Four Horsemen, Elmer Layden, Harry Stuhldreher, Jim Crowley and Don Miller. It happened in Palmer Stadium on a sunny October twenty-fifth and never before in my life had I spent such a frustrating, disappointing afternoon. We were beaten, 12-0, and the final score didn’t bother me — it was the way in which Rockne’s men handled us, particularly me.

The 1924 Princeton team was a better-than-average Princeton team. We had beaten Navy, we later turned back Harvard, 34-0 and lost to a sound Yale team, 10-0. Yet against Notre Dame I felt as if we were being toyed with. I was backing up the line and I don’t believe I made a clean tackle all afternoon. There would come Layden, or Miller, or someone. I would get set to drop the ball carrier in his tracks and someone would give me a nudge, just enough to throw me off balance, just enough pressure to make me miss. I played the whole game that way, giving a completely lackluster performance.

We were walking up the chute to the dressing-rooms after the game and I actually felt ready for another two hours of contact. I wasn’t tired, nor was I beaten down physically as I generally was after a big game. Others walking with me agreed. As we pieced together our individual reactions to our defeat, we began to see that we had met something new, something we had never anticipated. We, and I am writing this in retrospect, had been subjected to our first lesson in what might be called the science of football.

These Rockne-inspired thoughts stayed with me for a long, long time. I completed my studies at Princeton the following June and jumped directly to the New York Yankees for a summer try-out, which, if it proved nothing else, proved to me that I wanted no part of professional baseball and undoubtedly demonstrated to the Yankee powers-that-were that one Charles Caldwell was far from a polished ballplayer. Instead of staying with the minor league club to which I had been demoted, I rusticated for a period on a Georgia peach farm, wrestling with agrarian problems and with my own ideas about the future.

There was no getting around it. I had been sold — hook, line, and sinker — by Rockne and his kind of football. I wanted to coach and, more important at the time, I wanted to learn everything I could about coaching a sport in which there were apparently a hundred and one opportunities to advance new thoughts, to develop partially explored theories and to blend the traditional with the unorthodox. Just as football was entering the so-called modern era, I was an eager green pea, willing to try and yet not entirely sure that I had the qualifications for any kind of a coaching assignment.

As I did so many times before his death in 1933, I turned for advice to one of the finest men I have ever known, Bill Roper, my coach at Princeton and the person who still symbolizes for me all of the ideals and fine qualities that we like to associate with intercollegiate athletics. Bill, then one of the country’s veteran coaches, with nearly a quarter-century of experience behind him, was nearing the end of his long reign at Princeton and was one of the first to sense that football in the middle 1920’s was undergoing tremendous changes, none of which he endorsed.

Bill, you may recall, was a lawyer, a city councilman in Philadelphia and an insurance man — all in addition to being a wonderfully inspirational coach. He didn’t have any particular system, insisted that football was ninety per cent fight and will always be remembered for popularizing the slogan coined by Johnny Poe: “A team that won’t be beaten can’t be beaten.” Nonetheless, he clearly saw, possibly after the 1924 game with Notre Dame, that the football he had known and loved was not the same game that was being taught by perfectionists like Rockne.